Published: Oct 13, 2018

By Laura M. Holson

Ronnie Marmo didn’t set out to make a political play when he wrote and starred in “I’m Not a Comedian … I’m Lenny Bruce.” Instead, the actor wanted to depict the complicated style of the counterculture comedian and satirist, who died over 50 years ago. But many have read Mr. Marmo’s performance as a commentary on the Trump era.

Indeed, Mr. Bruce, whose acerbic and profane observations about society inspired generations of comedians who wanted to do more than just tell jokes, is having a pop culture resurgence. In addition to appearing in works for the stage, Mr. Bruce is also a recurring character in Amazon’s Emmy winning TV comedy, “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.” And over the summer, an exhibit about Mr. Bruce opened at The National Comedy Center in Jamestown, N.Y.

After Mr. Marmo’s play debuted in Los Angeles last year, its original six weeks stretched to a sold-out 15-month run. Audience members cheered when Mr. Marmo, onstage as Mr. Bruce, hollered about free speech and recounted the comic’s frequent arrests on obscenity charges in the early 1960s. The Off Broadway play begins previews in New York this month at the Cutting Room, a nightclub in Murray Hill. (It opens Nov. 4.)

Mr. Marmo sees similarities to his subject’s era: Free speech is once again under attack, Americans are divided over race and religion and protesters crowd city streets and the halls of Congress.

“Lenny Bruce is more relevant than ever when you consider the state of the country,” Mr. Marmo said. “His biggest thing was he hated hypocrisy.”

Had he lived, Mr. Bruce would be turning 93 on Saturday. But his ideas continue to provoke.

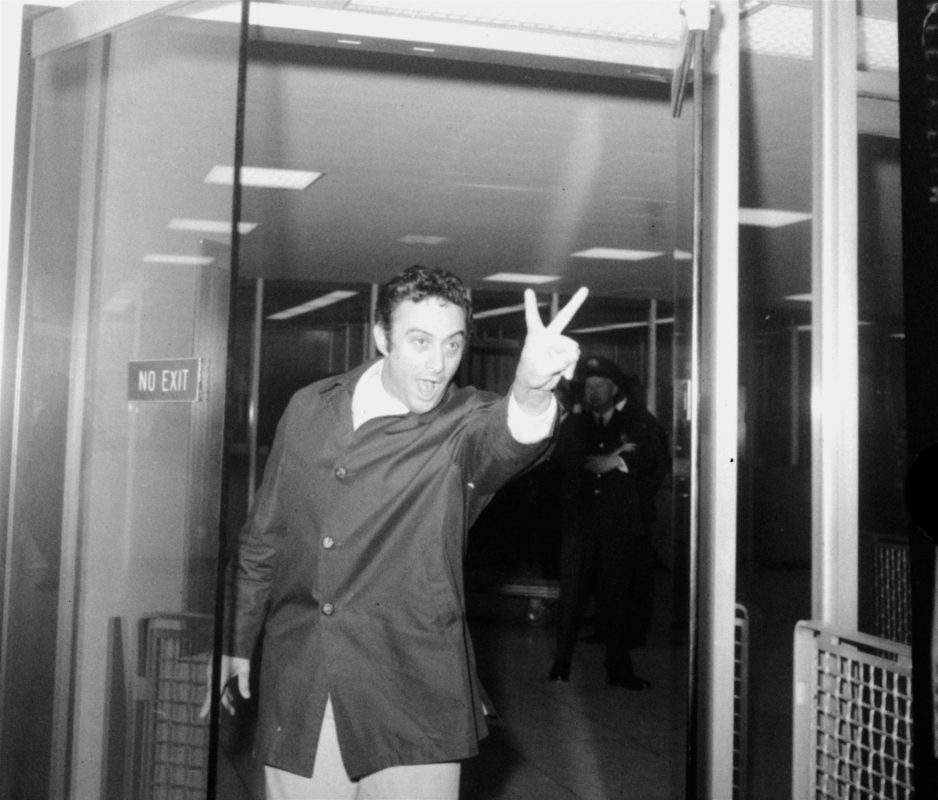

Mr. Bruce leaving New York’s Idlewild Airport after returning from Britain in 1963.

He was barred from entering London because his act was considered obscene.

CreditJohn Lindsay/Associated Press

Last year, Brandeis University canceled the production of a play about him. The Massachusetts school was accused of censorship, and the playwright, Michael Weller, pledged to produce his show, “Buyer Beware,” elsewhere.

“It is 2018 and my father is still talking,” said Kitty Bruce, Mr. Bruce’s daughter who founded the Lenny Bruce Memorial Foundation in 2008. “The fights are different, but the message is the same.”

Mr. Bruce was born in 1925 in Mineola, N.Y. His parents divorced when he was a boy, forcing him to move frequently between the homes of relatives. He joined the Navy in 1942, fighting in Northern Africa and Italy in World War II. When he returned to New York, he worked at a peanut butter factory and as an usher at the Roxy, according to a 1959 profile in The Times.

He followed his mother, the comedian Sally Marr, into life as a standup.

One of the creators of “Mrs. Maisel,” Amy Sherman-Palladino, told Vanity Fair last year that she had met Ms. Marr as a young girl. In the show Mr. Bruce’s character befriends Midge Maisel who, in 1958, is trying to break into comedy. “She was sort of the godmother to all the comics,” Ms. Sherman-Palladino said of Ms. Marr.

A 1963 Times headline.CreditThe New York Times Archives

In 1951, Mr. Bruce married a stripper and moved to Hollywood, where he played the burlesque clubs. (They later divorced.) But it wasn’t until the late 1950s that he earned a reputation as a spontaneous linguist who connected ideas and words in a style reminiscent of jazz musicians.

The Times described Mr. Bruce in 1959 as “a four-button mongoose” imbued with a streak of moral indignation. “The kind of comedy I do isn’t, like, going to change the world,” Mr. Bruce said in the interview. “But certain areas of society makes me unhappy, and satirizing them — aside from being lucrative — provides a release for me.”

By then he had begun to push cultural boundaries. As a guest on the Steve Allen show in 1959 he poked fun at kids sniffing glue to get high and at the actress Elizabeth Taylor for studying Judaism. It was among his tamer performances.

In Mr. Marmo’s one-man show, he repeats a famous nightclub sketch in which Mr. Bruce spat out a string of racial slurs about African-Americans, Jews and Italians. (Dustin Hoffman did the same sketch in the title role of the 1974 movie, “Lenny.”)

Mr. Bruce’s act was meant to render racially charged language meaningless, Mr. Marmo said. Even now it has the opposite effect. “One black woman in the back of room stood up and said, “That’s what we are doing now?” the actor recalled. “I have the audience talk to me all the time.”

In October 1961, Mr. Bruce was arrested in San Francisco on obscenity charges. In 1963, he was barred from entering London after arriving at the airport and referred to as an “undesirable alien,” according to news reports and historians. In April 1964, he was arrested at the Cafe au Go Go in Greenwich Village in Manhattan, then convicted on obscenity charges and sentenced to four months in jail.

A headline from Mr. Bruce’s arrest in 1964.CreditThe New York Times Archives

More than 100 poets, artists and editors protested the trial, saying Mr. Bruce was exercising free speech. (Mr. Bruce was pardoned posthumously in 2003.)

His court battles became a financial drain and hurt his ability to book shows, and in 1966 Mr. Bruce died from a morphine overdose in the bathroom of his Hollywood Hills home.

Mr. Bruce’s work remains controversial. Mr. Weller, the playwright and screenwriter whose play was canceled at Brandeis, said the university had commissioned “Buyer Beware” based on its extensive archives of the comic’s work.

In the play, the main character, Ron, seeks to perform a routine in the style of Mr. Bruce but faces student protests.

After he turned in a preliminary draft, Mr. Weller said, students and teachers complained. One student told The Boston Globe that the play portrayed black characters as “ridiculous and vicious.”

The irony of having his play canceled by Brandeis, his alma mater, was not lost on Mr. Weller, whose other credits include the movie scripts for “Hair” and “Ragtime.” “Part of the point of the play is that there are these political eruptions that start with something small and inadvertent,” he said.

Ms. Bruce said it took a long time to come to terms with the notion that her father’s comedy would be interpreted by others. “I was always terribly uncomfortable with people doing his material,” she said. “I can say, now, I’m really happy that they are. I don’t think that he will ever be forgotten. And I will make sure he is not.”

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page C1 of the New York edition with

the headline: It’s About @#&%! Free Speech. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper| Subscribe